|

Historical Background

|

|

Calabrian dress -

1800's

|

Between 1890 and 1930, over 5 million Italians

immigrated to the

United States (not to mention an equal number that immigrated to

Canada, Australia, Argentina and Brazil) - 80% of them were from southern Italy. Bruno and Marianna were part of

that great exodus. They

did not think of themselves as Italians though, because

Italy

did not exist as a country, as we know it now, until 1871. They were Calabresi

from Calabria. Other Italian immigrants considered themselves Sicilian, Pugliese, Abruzzese, or

Napolitan depending on what part of the "boot" they were from.

What we now call

Italy was, for centuries after the fall of the Roman Empire, a collection of

city states and provinces controlled by other European countries.

During the mid 1800s, Giuseppe Garibaldi headed a revolutionary movement

- the Risorgimento, to overthrow foreign rule and unify

all the provinces into

one nation. To

gain support for the rebellion, sweeping promises for a better future were

made to all the provinces. Those in the southern provinces felt they had

the most to gain and many young men from southern Italy rushed to fill the ranks of Garibaldis army.

They saw the chance to get revenge for years of harsh foreign

oppression (especially from the French) and to liberate themselves from

impoverished peasantry. The

rebellion was successful and the

Republic

of

Italy

was born.

It was said that, Italians are as attached to their soil as an oyster

to its rock. Why then would

so many of them, like Bruno, want to take their families and leave

everything they held dear - their homes, villages and farms the land

their ancestors had lived on for centuries, just when a brighter future

seemed right at hand? The

answer is tied to a number of significant political events, economic

problems and natural disasters that impacted southern Italy in the late 1800s.

The great promises of the Risorgimento were slow to come to southern Italy.

Northern Italy

was more industrialized, the people better educated and far better off

economically than the south. The southern provinces were rural, rustic and

had agriculture based economies. They had little industry and were isolated from the big cities

and centers of arts and science. Because of that, southern

Italians were generally considered low and backwards by northern Italians. Those differences, developed into longstanding regional

animosities and tension between the provinces.

Since the

northern regions

were already flourishing and prosperous, their interests became the main

focus of the Italian parliament. The

first extensive rail system in

Italy

connected the northern industrial city of

Turin

with

Paris, not

Turin

with

Naples. While the rest of the

country was advancing and improving the lives of their people, the south

was left to manage on its own. Opportunities

for a better life seemed farther and farther away.

A

number of natural disasters

also hit southern Italy

about this time. During the 19th

century, southern

Italy

was notorious as the most malarial area in

Europe. On top of that, a series of

cholera epidemics swept through the south

between 1884 1887 that took the lives of 55,000 people.

Worst of all, the provinces of Calabria and Sicily were hit with

four major earthquakes in quick succession -1894, 1905, 1907 and

1908. The quake of 1908 was the most devastating, also

producing a tidal wave that destroyed most

of the coastal towns in the Sicilian province

of

Messina

and much of

the southwestern coast of Calabria

The dead

numbered almost 100,000. The

tidal wave reached a height of 40 ft, and for five days torrential rains

totally flooded the

provinces. Many

of those who lived to tell the story interpreted the disaster as nothing

less than a signal from

Providence

and joined the migration of Sicilians and Calabrians to the United States.

America

looked very appealing. The

oysters were leaving their rocks.

To

"L'America"

In May 1895,

Giacomo Bruno Fuscà, then

30 years old, along with his older brother Domenico, 35, and two

cousins,

Giuseppe DeCaria

and Giuseppe Scuglia left the

village

of

Vazzano

and made their way to Naples where they boarded the passenger

ship, SS Britannia, that would take them to

America. Bruno left behind his wife Marianna Nicolina DePalma, 28, and three young sons Giuseppe Maria,

age 7, Domenico

Antonio, age 4, and Francesco Giovan Battista, age 1 -

Joe, Don and Frank. Marianna came from a good family

in Pizzoni, the next town. She was the daughter of

Giovan Battista DePalma and Caterina Donato.

On their Certificate of Marriage, Bruno is listed as a calzoliao

- a shoemaker, Marianna is listed as a filatrice - a weaver. Later records give

her the title "donna de casa" - literally, Gentlewoman of the

house. This was a title of respect, it did not simply mean a

housewife.

|

Vazzano

Town Crest |

Pizzoni

Town Crest

|

As a side note here,

both Bruno and his brother Domenico could read and write. The

passenger manifest for the SS Britannia states this and signatures, in their own hand, by Bruno and his two brothers

Domenico and Francesco are often found on Civil Documents in Vazzano where

they signed their names as witnesses attesting to births, deaths and

marriages in the 1880s and 1890s.

In fact, Francesco was the sindaco

mayor, of Vazzano during

the 1890s. The Civil

Records of marriages, births and deaths are revealing in other ways too

because they list the profession the person the Record concerns.

It is clear that our branch of the Fuscà family were members of the artisan class and

were well

educated for the time. Quite a few of our direct ancestors had the title Mastro

- master/teacher. They were not peasants without hope, fleeing to

America. They came for well thought-through

reasons.

Bruno,

Domenico and their cousins

arrived in the port of New York on June 13 and were processed through

immigration at Ellis Island. They then went by

rail to their final destination, Johnsonburg, Pennsylvania. They had been

sponsored by one of the families who had come over earlier, possibly

the Malfera family or, more likely, the DeCaria family. They recruited many young men looking to come to America from Vazzano, Pizzoni and

the nearby towns of San Nicola da Crissa and Vallelonga to work as laborers in the

then thriving, industrial town of

Johnsonburg - work, such as cutting timber, brick manufacturing or working

in the paper mills. The sponsoring families did more than simply bring over laborers

for local industry. They felt an obligation and responsibility to look

after their welfare. In fact, Caterina DeCaria, the matriarch of the

DeCaria family, was known as Queen

Caterina to the immigrants. When she died, her body was preserved in a

glass coffin and placed in a mausoleum. Today, 24% of the

population of Johnsonburg still

claims Italian ancestry.

Johnsonburg,

Pennsylvania in 1895

Bruno

did not stay in Johnsonburg long, maybe a year. He left Johnsonburg

and moved to Braddock. PA working as a laborer for the Pennsylvania

Railroad. In 1897 with the money he saved, he bought a two room

building at 1314 Montier Street in Wilkinsburg. The following

year, he sent for Marianna and the boys.

|

SS

Alesia |

Marianna,

Joe, Don, Frank came over with Bruno's nephew, Giuseppe Fuscà, 21, on the SS

Alesia.

The Alesia left out of the Port of Naples on

September 5, 1898 and arrived in New York on the 24th. The ships manifest shows

Marianna had the grand sum of $10 to her name!

In 1900,

Elizabeth

was born. A year later, Bruno

bought a house two blocks away at 1517 Montier Street. He built double storerooms

downstairs one for making shoes and boots and in the other, he sold

food and ice cream. The

store was simply referred to as Brunos. The

family grew with the arrivals of Catherine in 1902,

Jack

in 1904, Richard in 1908 and Vic in 1913.

The children worked in the store and the businesses did

well. In 1918, they moved to 1124 Maple Street

on the hillside above the store on Montier Street. Bruno

converted the old building below into a grocery and general merchandise store, where

he gained the reputation If Bruno doesnt have it, nobody does.

The store served the community for over 30 years.

Grocery store chains were coming

into the neighborhoods by the 1920s and automobiles were quickly

replacing the horse and wagon. To

keep pace with changing times and to keep his business interests thriving, Bruno

opened a gas station and garage.

Bruno died in 1933 at the age of

68 and Marianna the following year at 66.

They are buried along side Bruno's brother Domenico and his wife

Maria Carmella (Facciolo) Fusca, Mary Fusca and Salvatore J. Fusca

in Monongahela Cemetery, North Braddock, PA.

I would like to specially thank

Josephine Nuzzo Fusia for her help, knowledge and wonderful sense of humor.

I wish she was still with us. Much of

the details above came from her.

Mille grazie, zia

Josephine!

Si, il sangue tira.

Tom Fusia

_____________________________________________________________________________________

La

Calabria

____________________________________________________________________________________

OK, so where are Vazzano and Pizzoni ?

The surrounding countryside is beautiful with rolling

hills.

For photos click HERE

Vazzano and Pizzoni are small agricultural towns

(population about 1200 each) in Vibo Valentia Province, Calabria.

They are about a mile from each other. Calabria is the southernmost Region in

mainland Italy - The "Toe" of the "Boot".

It

is the ahh... fuchsia

colored Region on the map below -

|

|

Pillars of

a Nation

painting by

Jim Daly

_______________________________________________________

The

Myth of Ellis Island Name Changes

Immigrants'

surnames were changed

thousands of times, but professional researchers have found that name

changes were rare at Ellis Island (or at

Castle

Island

, which was the

New York

port of entry prior to

Ellis Island

's opening). The myth of name changes usually revolves around the concept

that the immigrant was unable to communicate properly with the

English-speaking officials at

Ellis Island. However, this ignores the fact that

Ellis Island

employed hundreds of translators who could speak, read, and write the

immigrants' native tongues. It also ignores all the documentation that an

immigrant needed to have in order to be admitted into the

U.S.

In order to be admitted into the

United States

as an immigrant in the late nineteenth century or later, one had to have

paperwork. Each immigrant had to have proof of identity. This would be a

piece of paperwork filled out in "the old country" by a clerk

who knew the language, and the paperwork would be filled out in the local

language, not in English (unless the "old country" was an

English-speaking country). The spelling of names on these documents

generally conformed to local spellings within the immigrant's place of

origin. Even if the person traveling was illiterate and did not know how

to spell his or her own name, the clerks filling out the paperwork knew

the spelling of that name in the local language or could sound it out

properly according to the conventions of the language used. Also, in many

countries one had to obtain an exit visa in order to leave. Again, exit

visas had to be filled out by local clerks who knew the language, and exit

visas were written in the local language.

A ship's passenger list had to be prepared by the captain of the ship or

his representatives before the ship left the old country. This list was

created from the travelers' documents. These documents were created when

the immigrant purchased his or her ticket. It is unlikely that anyone at

the local steamship office was unable to communicate with this man. Even

when the clerk selling the ticket did not speak the language of the

would-be emigrant, someone had to be called in to interpret. Also,

required exit visas and other paperwork had to be examined by ticket

agents before a ticket would be sold. The name was most likely recorded

with a high degree of accuracy at that time.

Next, the ship's captain or designated representative would examine each

passenger's paperwork. The ship's officials might not know the immigrant's

language, but they had to inspect the exit visa and the proof of identity.

They knew that immigrants would not be accepted into

Ellis Island

without proper documentation and, if the paperwork wasn't there, the

passengers would be sent back home at the shipping company's expense! You

can believe that the ship's owners went to great lengths to insure the

accuracy of the paperwork, including names, places of birth and travel

plans. It is believed that many more people were turned away at the point

of embarkation than were ever turned away at

Ellis Island

. In other words, most of those without proper documentation never got on

board the ship.

When the ship arrived at

Ellis Island

, the captain or his representative would disembark first with the

passenger list. The

Ellis Island

officials would then bring in interpreters to handle the interrogations.

These interpreters were usually earlier immigrants themselves or the

children of immigrants, and they all knew how to speak, read and write the

language of the immigrants.

The usual immigrant processing time was one to three days. During this

time, each immigrant was questioned about his/her identity, and all the

required documentation was examined in detail. Keep in mind that this was

not a quick two or three-minute conversation such as we have today at

international airports. In the days of steamships, the

Ellis Island

officials had the luxury of time. They could make leisurely examinations.

The questioning at

Ellis Island

would be done in the immigrant's native tongue. While the immigrant often

was illiterate, the interpreter doing the questioning always could read

and write the language involved.

Ellis Island

employed interpreters for Yiddish, Russian, Lithuanian and all of the

European languages. The immigration center in

San Francisco

did the same for all the Chinese dialects as well as Japanese, Korean, and

many more Oriental languages. Other immigration centers in

Boston

,

Philadelphia

,

New Orleans

,

Galveston

and elsewhere followed similar procedures.

Anyone who did not have proper paperwork (in the native language) showing

the correct name and place of birth was sent back. Many thousands were

sent back for identification reasons or for medical reasons or because

they did not have sponsors in the

U.S.

Most of the people who came through

Ellis Island

did so with correct paperwork showing the correct or at least plausible

spellings of their real names in their original language.

There were a very few exceptions, however. Occasionally war refugees were

admitted without much documentation. This was especially true in 1945 and

1946. A few others succeeded in falsifying documents in order to gain

admittance when they could not be admitted under their true identities.

Occasionally a child was admitted under the surname of a stepfather when

the name of the natural father would have been more appropriate. Nobody

can document the number of exceptions, but most professional researchers

believe that the number of exceptions was very small.

Once settled into their new homes, however,

anything could happen. Millions of immigrants had their names changed

voluntarily or by clerks or by schoolteachers who couldn't pronounce or

spell children's names. Some immigrants changed their names in order to

obtain employment. Many immigrants found it easier to assimilate into

American culture if they had American-sounding names, so they gladly went

along with whatever their neighbors or schoolteachers called them.

However, the records at

Ellis Island

remained in the original language.

For

more information about the myth that "the family name was changed at

Ellis Island

," look at the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization's Web page at:

http://www.ins.usdoj.gov/graphics/aboutins/history/articles/NameEssay.html

|

|

From

the book Polyglot Italy:

The Greeks In

Southern Italy

by Dr. Geoffrey Hull

In

ancient times

Sicily

and the

Italian

Peninsula

south of

Naples

were known collectively as Magna Graecia - 'Great

Greece

' because of the number and importance of the Greek settlements there.

The coasts of Apulia,

Lucania

,

Campania

,

Calabria

and eastern

Sicily

were first colonized by mainland Greeks in the eighth century before

Christ.

The expanding Roman Empire had annexed the whole of Magna Graecia and

Sicily

by 241 B.C., and while the Romans planted Latin colonies here and there,

on the whole they treated the Italian Greeks as confederates, respecting

their language and culture. In

Rome

itself Greek was employed as a second language and in the first Christian

centuries the city had a large Greek-speaking minority. Latin spread

through the Greek cities of the South as an administrative language but

Greek held its own as a literary medium and the speech of the common

people in many areas. At the height of the Empire Vulgar Latin had

inplanted itself as the vernacular only as far south as the Apulian towns

of Tarentum and Brundisium, and the river Crati in Bruttium (present-day

Calabria), the Salentine peninsula, lower Calabria and eastern Sicily

remained for the time being strongholds of the Greek language.

There is evidence that Greek continued to be widely spoken in

Calabria

(at least by the lower classes) until the Renaissance period. The

anonymous author of a French chronicle of the late thirteenth century

noted that "through the whole of

Calabria

the peasants speak nothing but Greek". In 1368 Petrarca

recommended a stay in the region to a student who needed to improve his

knowledge of Greek.

In the early sixteenth century Calabrian Greek was still vigorous in the

inland districts south of Palmi and Cittanova but by the close of the

seventeenth century it had receded into the Aspromonte mountains of the

southern tip of the peninsula, an area comprising hte towns of Cardeto,

Bagaladi, Motta San Giovanni, San Lorenzo, Melito, Condofuri, Roghudi,

Bova, Palizzi, Africo and Sant'Agata. For the next century and a half the

Calabrian Grecia (Greek-speaking zone) remained fairly stable,

until the Risorgimento and Unification unleased a new tide of Italian

linguisitic influence which accelerated the process of erosion. By the

1920's the ancestral language of

South Calabrians

could be heard only in the small rural communites of Bova, Amendola,

Condofuri, Galliciano, Roccaforte, Roghudi and Ghorio.

By the time they became citizens of the Kingdom of Italy in 1861, the

Italo-Greeks, mostly poor peasants, had long been severed from the

Byzantine religious traditions and from the mainstream of Neo-Hellenic

civilization, The modern Italiot renaissance began in the Salentine Grecia

through the efforts of Vito Domenico Palumbo (1857 - 1918), a native of

Calimera, who endeavoured to re-establish cultural contacts with

mainland Greece. Although excluded from the churches, schools and

government offices, Greek began to be taught in some villages in the

decade following World War II on the initiative of private individuals. In

1971 the Unione dei Greci dell'Italia meridionale was founded to

foster relations between the Calabrian Greeks (today numbering only 5,000)

and the 15,000 Salentine Greeks. At least three bilingual journals devoted

to the Griko language are now in circulation, and a number of

mainland Greek intellectuals and cultural bodies have taken an interest in

the welfare of their trans-Ionian brothers. Nevertheless, in spite of

these developments, Italo-Greek continues to be ignored the the Italian

government. Furthermore the Calabrian Grecia, already in an advanced state

of decay, suffered a serious setback when the floods of 1970 and 1972

forced the evacuation of Roghudi and Ghorio. The inhabitants of these

villages have since been resettled along the Ionian coast and in Reggio

where the language has little hope of survival.

Ample traces of the recent Greek past of Calabria, Salento and

north-eastern Sicily remain in the local Neo-Italian dialects (the Romance

speech that replaced Greek), and in regional surnames like Argurio

('Silver coin'), Calabro ('Calabrian'), Calo, Cala ('good'), Cefali

('head'), Chiriaco ('lordly'), Condro ('fat'), Dascoli ('Teacher'), Foti

('bright'), Lagana ('greengrocer'), Lico ('wolf'), Macri ('long'),

Papandrea ('the priest Andrew'), Patera ('father'), Pangallo ('very

good'), Schiro ('hard'), Sgro ('curly-headed'), Spano ('beardless'), Trano

('adult'), Tripodi ('tripod'). The Hellenisms in the modern South

Calabrian dialect include such common words as ciaramide 'tile',

ahjeri'dish-rag', crasentulu 'worm', capura 'pail', scifu 'trough', tripu

'hole', cudespina 'old woman', cuddaraci 'Easter bun', fusca 'bran',

hasmiari 'to yawn', milinghi 'temples', spissida 'spark', cilona

'tortoise', petula 'butterfly', praia 'beach', rosacu 'frog', zafrata

'lizard', and zimmaru 'ram'. South Calabrian offers many examples of Greek

syntax in Romance dress, for example the periphrastic construction that

replaces the Italian infinitive, e.g. vogghiu mu vajo 'I want to go'

(literally: "I want that I go") = Bova Greek thelo na pao (It.

Voglio andare), vinni mi ti dugnu 'I came to give you' = irta na su dhosu

(It. Venni a darti). Similarly, the use of the preterite tense instead of

the Italian present perfect betrays a recent Greek substratum, e.g. comu

mangiasti? 'how have you eatern?' = local Greek pos efaje? (It. Come hai

mangiato?), ci facistivu? 'what have you done?' = ti ecamete (It. Che cosa

avete fatto?).

|

|

Description of Calabria in 1589

By

Gabriel Barrius Franciscanus

CALABRIA, a country of Italie in form and

fashion not unlike a tongue, lies between the upper and lower seas. It

begins at the lower sea (the Greeks call it the Tyrrhen sea, the Romans

the Mediterranean or Midland-sea) from the river Talao, which runs into

the

Bay

of

Policastro.

At

the upper sea (the Ionian sea is what the Greek call it), the river Siris

(also once called Senno) flows along until it comes to the straights of

Faro di Messina and the city of

Reggio

. And then, being divided into two by the mountain range Apennine (here

they call it Aspromonte) it ends at two capes or promontories, one called

Leucopetra (by them Capo de Leucopetra), the other Lacinium (vulgarly by

them called Cabo delle colonne or Cabo dell'Alice).

Not

only the plains and the fields, but even the hilly places, as is the case

in

Latium

or

Campania

are well provided with water.

Whatever is necessary for the maintenance of mans life is yielded by this

country in great abundance, so it needs no foreign commodities but is able

to live of what it provides by itself. In general,

Calabria

has a good and fertile soil, and

it is not bothered by

Fens

, Lakes and Bogs, but is always green, affording good pastures for cattle

and excellent grounds for all sorts of grain. The fountains and brooks are

numerous, and fairly clear and wholesome.

The

sunny hills and mountains, open to every cool blast of wind, are

wonderfully fertile for corn, vines and trees of various kinds, which

provide great profit to its inhabitants. The valleys are pleasant and

fruitful. The shady groves and woods afford many pleasures and delights.

The excellent meadows and pastures are richly covered with herbs and sweet

smelling flowers, and ever running streams. And among other things, here

is plenty of wholesome food with which they feed and fatten their cattle.

Here also grow many medicinal herbs of sovereign virtues, against various

different diseases.

It

brings forth various plants, such as the Plane tree, Vitex or Agnus castus,

the Turpentine tree, the Olive tree, Siliqua Silvestris, Arbute or

Strawberry tree, wild Saffron, Madder, Licorice, and Tubera or Sowbread.

It also has some hot baths, continually issuing from their springs, which

cure aches and many other similar illnesses. In various places there are

salt water springs of which they make some kind of brine or pickle. It is

well watered by many fine rivers, and those are well provided with various

kinds of fresh water fish. The sea on each side also yields plenty of

fish, tunas as well as sword-fishes and lampreys. In many places here the

best Coral is found, both white and red.

Here

hunting and hawking is most pleasant, for in these places various

different sorts of wild beasts live, and as many birds and fowls breed and

build nests here. Then there are wild boars, deer, hinds, goats, hares,

foxes, lynxes, otters, squirrels, martens, badgers, ferrets, porcupines,

and tortoises, both of the water and of the land. It is everywhere full of

fowls, pheasants, partridges, quails, wood-cocks, ring-doves, crows &c.

as also of many kinds of hawks. It maintains some herds of cattle and

flocks of sheep and goats. It breeds excellent horses, very swift and of

great courage.

Metals were found here in old times, and to this day it still abounds with

various kinds of minerals, having indeed everywhere mines with gold,

silver, iron, salt, marble, alabaster, crystal, marcasite, red lead or

vermilion, copper, alume, brimstone &c. Also many kinds of corn,

wheat, silage, beer-barley, rye, trimino (we call it Turkey wheat I

think), barly, rice, and sesame, all in infinite quantities. It also

abounds with all kinds of pulse (legumina the Romans call it), oil, wine,

and honey, all the best of their kind.

There are here everywhere orchards full of oranges, lemons and Pome lemon

trees. They also make plenty of excellent silk here, far better than any

kind of silk made in other places in Italie. The cotton bush (Gossipium)

grows here plentifully. But what shall I say about the kind temperature of

the air? For here the fields both in winter and summer are continually

green. But above all things, there is nothing which makes my point more

soundly than that airy dew or heavenly honey which they call Manna that

comes down everywhere from above, and is here gathered in great abundance.

So that which the Israelites in the wilderness admired and considered as a

strange wonder, is here provided by kind nature of her own accord.

It

is also adorned with many good market towns, where markets and fairs are

held at certain times of the year. In some places here the ancient custom

of the Romans is still preserved at funerals and burials of the dead,

where a chief mourner (Praefica they call her) is hired to go in front of

the mourners guiding their mournful rituals, keeping time to their howling

lamentations. The funeral being done and all ceremonies performed, the

dead persons friends and kindred, bringing their own food and picnic gear,

banquet all together at the dead persons house.

The women of this country as a matter of course, out of modesty or because

the water of this area is good and wholesome, drink nothing but water. It

is considered to be a shame for any woman to drink wine, except if she is

very old, or is in childbirth.

|

|

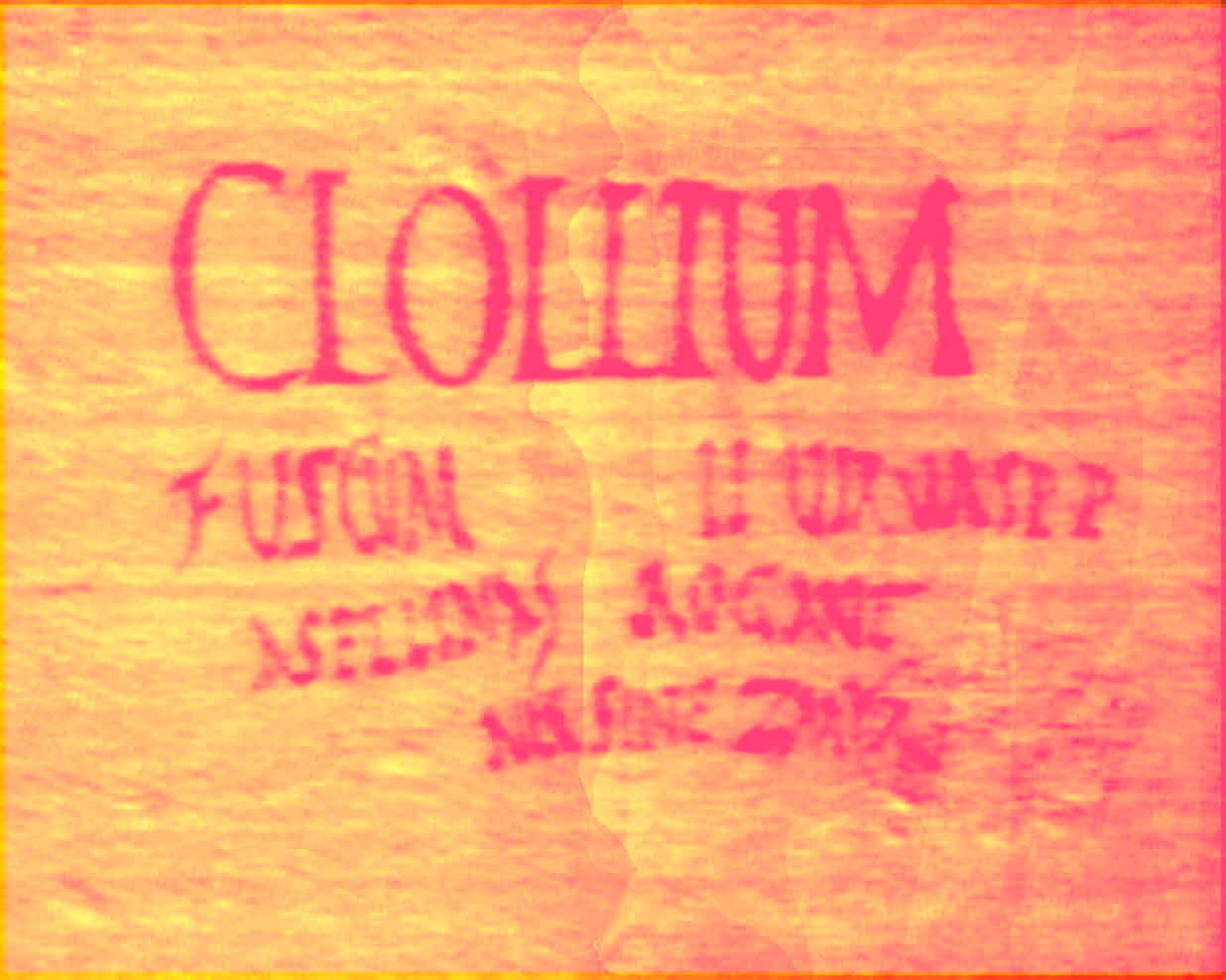

Political

Graffiti

from Pompeii 79 A.D.

Translation:

"Asellina

and her girls urge you to vote for Gaius Lollius Fuscus

for

Minister of Public Affairs"

Note: Asellina

ran an "entertainment house" in Pompeii. This

was written on the outside wall of her establishment.

|

|

|

|

The Fusia and Fuscà

Families

The Fusia and Fuscà

Families

![]()